Report: Zed Adams on Color Relativism

Summary of Zed Adams (The New School for Social Research) lecture: "How to Argue for Color Relativism" (Jan. 19, 2009)

Color has long been a subject both fascinating and notoriously difficult in theories of perception. This is true not only for philosophy, including both the phenomenological and analytic schools of thought, but also for psychology and, more recently, the cognitive sciences. Drawing upon these various traditions, Zed Adams' aim is to present a fresh look at some of the quandaries of color.

For the sake of brevity, I will try to focus on what I understand to be the three key questions about color that Adams addressed in his talk. Each of these questions is in turn a requirement that he believes a theory of color must address. Next, I will briefly summarize the model Adams proposes for addressing those requirements. In this reconstruction I will thus not be following the original order of Adams' presentation, and will also skip most of his interesting engagements with other theorists of color.

The first key question regarding colors is whether they are subjective experiences that we have when we perceive objects or objective properties of these objects. To a large extent, this question continues the traditional debate about primary versus secondary qualities. The challenge Adams seems to take upon himself is that of finding a way of talking about colors that captures both these dimensions as well as their interrelatedness, rather than one that reduces one of them to the other. We need to explain how color is experienced as a quality of an object, but also refrain from reducing this "of" to a subject-independent quality of the object.

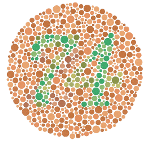

The second question is how to explain inter-personal variation in color perception, namely the fact that different people can sometimes perceive the same object—or even a simple color patch—as being of different color. Such variations can be of different kind. For instance, they can be differences in the vocabulary employed to describe colors, but there are also inter-personal variations that are the result of physiological differences, such as color blindness.

The third question or requirement is to take note of the fact that, on the one hand, the color of the same object looks different depending on various viewing conditions, and yet we can say the object has a single color. Think of how the same object changes its color under different lighting conditions, say throughout the day. At the same time, if we take a familiar object that has a distinctive or "standard" color, so to speak—e.g. a blank sheet of paper or an orange—and we showed that object to different people under different lighting conditions, it is likely they will all say it is the same color—white and orange respectively.

Of course, there is nothing unusual about these observations. But like many aspects of perception, it is precisely their everyday nature that poses a challenge to a theoretical definition or explanation of color. The challenge is to describe color precisely as something that can both be experienced differently under different circumstances and also be coherently identified as being the same color throughout those differences.

Adams' proposal for tackling these requirements is to argue that we need to distinguish between what he calls object color and matching color. To illustrate this distinction he referred to the rather standard phenomenological example of shape perception. Let us take a simple three-dimensional object like a cube. When we look at a cube we always see it from a particular angle, and thus cannot grasp its entire shape in one "look". For instance, when we perceive a cube from its side it appears as a flat square. At the same time, though, we know that by moving our gaze the cube would change its appearance. Once we know enough about viewing cubes, we can say that we are capable of distinguishing between what Adams would call its object shape and its various matching shapes, which depend on our line of sight. Likewise, we can say that an object has an object color, which appears or is experienced as different matching colors under different viewing conditions. The way to correlate the two is to say that our judgment of color depends upon us being aware of these viewing conditions. Sometimes we are also aware, in the sense of having practical knowledge, of how we can manipulate these conditions: for instance, when we want to discern the color of an object in a dark room, we know that we need to turn on the light in order to get a better view. Another way to put this is to say that when we talk about the object color of a particular object, we mean its color under what are taken to be normal viewing conditions. And these normal conditions already take into account a certain degree of variance, such as variance in lighting conditions.

Seeing as object-colors rely on a more-or-less stable viewing environment, we can then go on to say that if the same object is viewed in two environments that are different enough from each other, there is room to talk about this object having two object colors. Here Adams refers to an example by the philosopher of language John Austin. Suppose there is a fish that, when caught and taken outside the water, has a certain color, but when viewed in its natural habitat, say a thousand feet deep, has a different color. What should we say is the color of the fish? According to Austin, there is no "right" answer here. According to Adams, however, the correct thing to say is that it has two object-colors. The key point is that there is a radical enough difference between the two viewing environments. By "radical" I understand Adams to say that when we talk about colors we always take into account a certain degree of variation in matching color. Thus, in the case of Austin's fish, when viewed outside the water at different hours of the day, we would say that it exhibits different matching colors while having the same "terrestrial" object-color; and when viewed at depths between, let us say for the sake of the example, 900 and 1100 feet, we would say it exhibits different matching-colors while retaining the same "deep water" object-color.

According to Adams, the advantage of this approach is that it is able to stir clear of the two "reductive" approaches to color. Namely, on the one hand, the approach that tries to explain color in a non-experiential, purely "objective" way; and, on the other hand, the approach that claims there is nothing more to color over and above our experience. One of the keys to Adams' alternative is his attempt to balance between a phenomenological approach and a linguistic-analysis approach; namely between an analysis of the structure of color experience and an analysis of color judgments.

(Summary by Naveh Frumer)