[Report] "Two Perspectives on the ‘Thing’ in Poetry: Where Fenollosa and Pound Diverge"

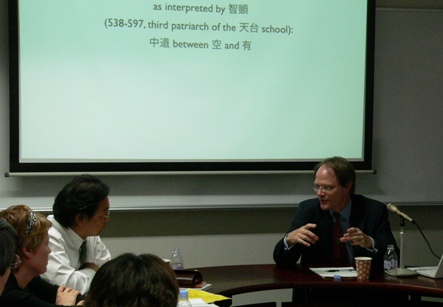

On May 25, 2009, UTCP and the Todai-Yale Initiative invited Haun Saussy, Professor of Comparative Literature at Yale University, to give a talk titled “Two Perspectives on the ‘Thing’ in Poetry: Where Fenollosa and Pound Diverge.”

Ernest Fenollosa’s work on Chinese and Japanese language is best known through Ezra Pound’s edition, published in 1919 in the U.S. Professor Saussy published The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry: A Critical Edition (2008), which includes his edited version of Fenollosa's essay "The Chinese Written Character as a Medium of Poetry.” In this book, Professor Saussy added what Pound in his version of Fenollosa’s essay omitted. In his presentation, Professor Saussy showed us the difference between Pound’s and Fenollosa’s understanding of “thing” in Chinese poetry.

From Fenollosa’s essay, Pound understood the meaning of “things” in Chinese poetry to lay in their concreteness. He, like Fenollosa, saw Chinese characters as “vivid shorthand pictures of the operation of nature”, which reflect the cause and effect of the natural world. Pound used the concept of “things” in Chinese poetry as part of the artistic modernism movement to revolt against the European abstract categorization of the world. According to Professor Saussy, however, Fenollosa’s writings, which Pound either deleted or ignored, show that Fenollosa was actually interested in the abstraction of “things” rather than their concreteness. Professor Saussy pointed out that here Fenollosa’s thinking on “things” resembles Kogen epistemology. He speculated that Fenollosa’s writings must have been influenced by Abbot Sakurai Keitoku, who taught Fenollosa Tendai Buddhism, as well as by Okakura Tenshin, his student at the former Imperial University in Tokyo.

Unlike Pound, Fenollosa’s interests went beyond art and aesthetics. He was interested in a mutually transforming encounter of East and West by means of religion, philosophy, and ultimately humankind. Such an idea was deleted in Pound’s writing, but eventually accepted by post-modernist artists. Fenollosa’s interests in ideas of far away people shows that “globalization” is nothing new. Professor Saussy noted that Fenollosa’s curiosity and receptiveness are noteworthy.

After the talk, there were questions from the audience on what “East” and “West” meant for Professor Saussy. Where did “America,” where Fenollosa was from, fit on the geopolitical map? Was it in the same framework as “Europe”? Since religion is a modern creation, how can we think of Buddhism as part of the “East”? Japanese intellectuals at the time of Okakura Tenshin thought of Japan as “Eastern”, as it was created in the “West.” These two categories are still accepted and reproduced in Japan today. How can we ever overcome this dichotomy? To these questions Professor Saussy responded that “East” and “West” were used by Fenollosa, but we can be critical of them today. However, we should give Fenollosa credit for his effort to understand the ideas of people from far away places. In thinking about intellectual history and art history in the twentieth century, it will be important to consider relationships such as Fenollosa had established. At the end of the talk, Professor Saussy remarked that he hopes to continue the intellectual exchange between Yale and Todai through the Yale-Todai Initiative.

Reported by Noriko Kanahara