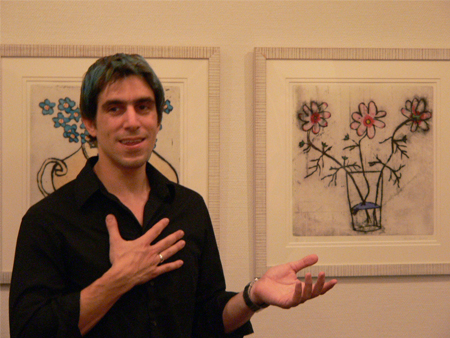

[Report] Jesse J. Prinz Lecture Series

We held a series of lectures by Prof. Jesse. J. Prinz (The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) for six days from the 14th to 23rd of July.

[Lecture 1: July 14th, 2008]

The first lecture, “The Emotional Basis of Morality: Philosophical Theories and Psychological Evidence,” was held on the 14th of July. In the lecture he presented his basic position on morality. I will report the lecture in the following.

Prof. Prinz endorses Emotionism which regards emotions as playing essential roles in morality. Traditionally, Hume endorsed this position, but Kant, who argued that moral judgments should be made exclusively by rationality, opposed to it.

According to Prof. Prinz, Emotionism has two faces: Epistemic and Metaphysical Emotionism. Epistemic Emotionism is the thesis that we need emotions to recognize moral facts, that is, moral concepts are essentially tied to emotions. Epistemic Emotionism seems plausible based on daily observations about our moral judgments because a certain emotion accompanies when we make a moral judgment. For instance, we have a feeling of indignation when we judge infant abuse is wrong, and we have a feeling of disgust when we judge incest is wrong.

But people who oppose to Epistemic Emotionism claim there can be an amoralist who lacks all emotions but can make moral judgments as do ordinary people. Against this objection, Prof. Prinz appealed to psychological evidence and showed the amoralist is impossible and moral judgments and emotions are closely related.

Although he introduced many experiments and facts, I here describe only the case of psychopathy. Psychopaths are those who chronically commit serious crimes without feeling any guilty. They cannot have strong negative emotions, but are sufficiently intelligent. Some might think they are real amoralists because they agree to common value judgments, but they are not. They cannot understand a distinction between conventional rules such as “Do not run in a corridor” and moral rules such as “Do not kill a person”. Psychopaths do not understand morality in a full sense. Their existence indicates normal moral concepts require emotions.

On the other hand, Metaphysical Emotionism is the thesis that moral properties are essentially tied to emotions. There are some meta-ethical theories: anti-realism such as Error Theory and Expressivism, and realism such as Objectivism that claims moral concepts refer to objective properties in the world. Prof. Prinz adopts a realist but subjectivist view: moral concepts refer to reaction dependent properties. Let us take a property of being delicious as an example. The fact that chocolate is delicious is a worldly fact, but it depends on a perceiver who feels a chocolate is delicious. In the same way, the fact that infant abuse is wrong is also a worldly fact, but it depends on a moral subject who has negative sentiments toward infant abuse. A realist and subjectivist position almost automatically entails moral relativism; there are many moral facts in accordance with our emotions. This is one of the interesting points of Prof. Prinz’s position.

This is Prof. Prinz’s basic position on morality. In closing, I would like to emphasize an innovative aspect of his philosophy. It is that he takes empirical data more importantly than traditional philosophy. He discerns serious problems of philosophical methods relying on intuitions. First, a philosopher’s intuitions are not so universal as philosophers assume. They underwent special training, and hence their intuitions differ from ordinary people. Thus, philosophers have to empirically investigate folk intuitions. Second, intuitions are often fallacious. Intuitions about our own mental processes are not always right. We cannot grasp real mental processes by our first-person point of view. According to Prof. Prinz, the connection between emotions and moral judgments cannot be revealed only by armchair philosophy, and empirical investigations are also required. Based on this idea, Prof. Prinz referred to psychological evidence as I mentioned above. Besides, he does not only consider empirical data, but also thinks philosophers should conduct experiments. Philosophy which adopts such a method is called experimental philosophy, and it is attracting much attention these days.

Thus moral philosophy of Prof. Prinz is a stimulating theory which connects the sciences and philosophy of morals and emotions. After the lecture, we had an animated discussion. The topics were ranged from the content of the lecture to experimental philosophy in general. The series of lectures touched off successfully.

Ryoji Sato (UTCP research fellow)

![]()

Download (MP3, 43.8MB)

Open another window 【Windows Media Player】 【Real Player】 【QuickTime】

[Lecture 2: July 15th, 2008]

This is a summary of Professor Prinz’s second lecture, whose title was “What neuroscience reveals about moral judgment”. In this lecture, he emphasized the importance of emotion in moral judgment. Also, he argued that neuroscientific evidence corroborates this point.

In our daily life, when we decide something, we judge based not only on one norm, but on more than one norm. In the latter case, we may be in a quandary, and so it may be difficult to judge something correctly. For example, suppose that many people will survive in exchange for killing a person in front of you. In this case, there is a conflict between the norm that killing someone is wrong and the norm that making more people survive is good, and many factors more than rational inference are involved with deciding our behavior. Prinz insists that a moral judgment is affected not only by the ability of rational reasoning, but also by emotion or feeling.

Traditionally, there is a conflict between the rationalist idea that moral judgment mainly comes from rational reasoning and the intuitionalist idea that moral judgment is ultimately based on irrational emotion. The recent scientific study of decision-making mechanism is revealing the importance of emotion which intuitionalists have emphasized so far. For example, medial prefrontal cortex is necessary for rational judgments, insular and cingulated cortices are associated with emotional experiences and moral judgments, and orbit frontal cortex is associated with emotional decision-making. These facts show that a rational inference is considerably influenced by emotions.

But Prinz does not argue that the traditional intuitionalist idea, in which the importance of rational reasoning is not taken into consideration, is immediately supported by neuroscience. Rather he argues that moral judgment needs the cooperation of emotion and reason. One of many arguments which Prinz presents for this cooperation is the dual process model, and this model, according to which rational-reasoning and emotional processes are converged in a decision-making, is supported partly by neuroscientific evidence.

According to Prinz, neuroscientific evidence is pretty week right now, but it is very significant to dispel deep-going misconceptions, on the basis of scientific research.

Yu Nishitsutsumi (The University of Tokyo)

![]()

Download (MP3, 45.1MB)

Open another window 【Windows Media Player】 【Real Player】 【QuickTime】

[Lecture 3: July 17th, 2008]

In third lecture, Professor Prinz investigates cultural aspects of morality. Some cultures emphasize “equality,” some “equity,” and others “need.” Prof. Prinz points out that each culture has different features of morality. So we have to ask where morality comes from and whether biological theories of morality are superior to cultural ones. Prof. Prinz embodies these problems as follows: Is morality really universal? And is it really innate? He shows many examples that urge us to say “no” to these questions. In this lecture, I understand his provisional answer as follows: although evolutional theory may be important for moral norms, cultural and environmental factors may be more important.

Koji Tachibana (The University of Tokyo)

![]()

Download (MP3, 47.8MB)

Open another window 【Windows Media Player】 【Real Player】 【QuickTime】

[Lecture 4: July 18th, 2008]

The 4th lecture by Jesse J. Prinz was about moral emotions. In the first three lectures, he claimed that morality is based on our emotion, showing evidence from psychology, neuroscience, and anthropology. In this lecture, he turned his focus to the questions about emotions themselves and about their relation to morality.

In the beginning of the lecture, Prinz posed two questions: first, what are emotions? second, which emotions matter for morality?

As the answer to the first question, Prinz defines an emotion as the perception of bodily changes. He gives examples that support this definition: ANS drugs directly working on the nervous system and causing emotions; facial feedback, i.e. induction of emotion by merely changing one’s facial configuration; brain-imaging studies revealing that brain areas regulating emotions are associated with bodily perceptions.

Then Prinz examined two oppositions to his definition. The first opposition concerns the meaningfulness of emotions. Emotions seem to have some meaning. For example, it can be said that an emotion of joy means that there is something good, and an emotion of sadness means that there is something bad. To explain such aspects of emotions, we should perhaps define emotions not as mere perceptions but as some kind of thoughts.

Prinz refutes this opposition by showing that noncognitive emotions can have meanings or representational contents. According to him, our emotion represents the relationship between us and the world. Our capacity to percept our bodily changes enables us to know through emotions what kind of relation the world has to us. It can be said that, in the history of our evolution, this capacity was selected for representing to us the relationship between us and the world. Hence, the capacity of perception of bodily changes has the function of representing the relationship between us and the world by causing emotions. (Here, the word function is an abbreviation of the term teleological function, which is used by such philosophers as Fred Dretske and Ruth Garrett Millikan. A teleological function is a function, ascription of which is based on the history of selection.) This function enables us to explain the meaning of emotion.

The second opposition to Prinz is that we do not have enough bodily states to characterize a rich variety of emotions. As a counterargument, Prinz points out that basic emotions can be blended to make various complex emotions, and that emotions can be differentiated according not only to bodily states but also to the features of the world represented.

After refuting two oppositions above, Prinz went on to the second question: which emotions matters for morality? In relation to this question, it is important to distinguish between an emotion and a sentiment. A sentiment is a disposition to cause emotions corresponding to a context. Moral emotions are, in fact, the emotions that are derived from moral sentiments.

Take an example of waterboarding. Waterboarding is a kind of torture, so it acts on one’s negative sentiments. What kind of emotion is derived from this sentiment depends on a context. If the context is that others are waterboarding someone, anger will be derived. If the context is that one is waterboarding someone, unwillingly following the order of his/her superior, guilt will be derived. As opposed to these examples, a sudden irritation for no apparent reasons is not a moral emotion, because it is mere anger which is not derived from a moral sentiment. Moral emotions are emotions that are based on moral sentiments.

The kind of moral emotions differs, depending on whether one is the violator or the violated in a situation that causes emotion. For instance, toward others’ transgression against persons, one has anger; toward others’ transgression against community, one has contempt; toward his/her own transgression against nature, one has shame. The neural correlates of these moral emotions have come to be known through neuroscientific studies. Also, it has been made clear that, among various cultures, more or less the same kind of moral emotions can be seen in the same context (even though there are some differences in emphasis).

Emotions are the basis of our morality. To explicate the moral judgment based on emotions in greater details, more psychological or comparative studies are needed.

Haruka Tsutsui (The University of Tokyo)

![]()

Download (MP3, 46.9MB)

Open another window 【Windows Media Player】 【Real Player】 【QuickTime】

[Workshop 1: Morals, Emotions, and Evolution]

The structure of the workshop was this. First, RAs and postdocs of UTCP made their comments on or asked questions to Professor Jesse Prinz. Second, Prof. Prinz replied to them. Third, we had a general discussion. The speakers were Eisuke Nakazawa, Ryoji Sato, Taichi Isobe, Maika Nakao and Yu Nishitsutsumi. I report parts of their presentations, Prof. Prinz’s replies, and the general discussion.

Comments and Replies

The title of Eisuke Nakazawa’s presentation is “Emotion and Natural Kinds”. While he agrees with Prof. Prinz that emotions are a natural kind, he contends there are some troubles with this position. This is because some subcategories of emotions seem to exist based on mechanisms that do not correspond to Prof. Prinz’s embodied appraisal theory of emotions. For example, happiness seems to be explained by the reward system of the brain. Hence it requires difficult tasks which need many steps of experimental investigations to explain whether each emotion is a natural kind.

The point of Prof. Prinz’s reply to Nakazawa seems to be this: since there are many problems with subcategories of natural kind not only in emotions but also in general, his answer would vary depending on what ontology of natural kinds he takes.

The main concern of Ryoji Sato’s presentation, whose title is “Can we really imagine emotions?” is the debate on emotions between cognitive and non-cognitive theories. According to the cognitive theory, to form an appraisal judgment is a precondition to have an emotion. Sato finds Prof. Prinz’s position in his Gut Reactions problematic. Although Prof. Prinz argues that almost all emotions are non-cognitive, he at the same time insists that they are cognitive in imagination. But this raises a question of whether emotions in imagination are really emotions.

In his reply, Prof. Prinz points out that Sato’s argument heavily depends on our intuition. Prof. Prinz suggests that this problem will be solved through empirical investigations, such as the observation of the brain activation in imagination.

Taichi Isobe’s presentation is concerning the evaluation or progress of morality. As to this point, Prof. Prinz emphasizes the importance of extra-moral standards, because moral standards only affirm our current moral values and reject other ones. Isobe’s questions are as follows: are the extra-moral standards more foundational than the moral standards? and do the extra-moral standards include subjective aspects?

In reply, Prof. Prinz argues that the extra-moral standards are also subjective and relative, and not more foundational than the moral standards in the light of holism. But there is asymmetry. Although morality often serves the extra-moral values, the inverse is not likely. In this respect, the extra-moral values have functional priority. Yet, sometimes morality influences the generation of extra-moral values.

The title of Maika Nakao’s presentation is “Is Emotions Reduced by Technology? A Consideration on the Trolley Cases”. It is well known that in the trolley cases, personal bodily contact with others crucially affects the subject’s moral judgment. The judgments vary between the case of pushing a fat man from a bridge and the case of manipulating a lever from a distant place. The actions such as manipulating a lever or pushing a button are based on technology. In this sense, technological developments must influence our emotions and moral judgments. In the light of this view, Nakao mentions a historical example of American’s atomic bombings. And she asks whether technological developments can reduce our moral struggle when we make moral judgments.

Prof. Prinz optimistically replies to Nakao’s comments and states that technological development serves morality. First, there is the fact that there is more violence in pre-modern societies than in our society. The easier killing comes, the less it happens. Second, information technology serves humanity. This is because, for example, it is available to free journalists and seems to bring the world together.

The title of Yu Nishitsutsumi’s presentation is “A Question about Prinz’s Argument against Evolutionary Ethicists”. Prof. Prinz criticizes evolutionary ethicists who insist on the priority of evolved norms by natural selection. He argues that moral norms are not products of natural selection, rather culture shapes all norms. According to Nishitsutsumi, however, such a hypothesis must be confirmed ultimately by the existence of the neural system that allows us to acquire evaluative skills through our social relationships. That’s why her question is this: what is the most important evidence for Prof. Prinz’s hypothesis?

Replying to Nishitsutsumi, Prof. Prinz argues that the findings of social learning in neuroscience and behavioral science are now quite limited and not enough, still he believes we will acquire useful findings in the future. He claims we will discover a neural mechanism underlying our cultural learning.

General Discussion

We talked about several points in the general discussion. I am particularly impressed by a series of debates below. To begin with, can robots have emotions? Prof. Prinz claims that robots can have common emotions with humans at the level of function. This requires robots to have their own bodies because the role of emotions is to detect changes in our body. Then, what should we think about a body? What is the extent of a body? When we connect a human with a computer, does this mean the computer becomes part of the body? Or what should we think about Merleau-Ponty’s theses of the extended body? Thus, starting with debates on morality, we reach the ontology of the body. This general discussion enabled each of us to find various points and tasks. As a whole, we had a very satisfying workshop.

Ryo Uehara (The University of Tokyo)

[Workshop 2: Moral Relativism]

The second workshop with Prof. Prinz was held on July 23rd. In the workshop, Japanese young scholars gave short presentations about Prinz’s philosophy and then Prinz responded to their criticisms and questions.

The first presenter was Kei Yoshida. The title of his presentation was “Moral Relativism, Tolerance, Fallibilism: A Problem with Jesse J. Prinz.” Yoshida advocated moral fallibilism inherited from Karl Popper and argued against Prinz’s relativism.

The second presenter was Haruka Tsutsui. The title of her presentation was “Individual Relativism and Group Relativism.” Tsutsui pointed out that there is a serious tension between individualistic and collectivistic aspects which are both found in Prinz’s constructive sentimentalism.

The third presenter was Ryo Uehara. The title of his presentation was “Skeptical Comments on Prinz’s Holistic Methodology of Moral Progress.” Uehara addressed methodological problems which lie behind moral progress and then claimed that processes of moral revision should be socialized.

The last presenter was Mineki Oguchi. The title of his presentation was “Repositioning the Genealogy of Morals.” Oguchi insisted that Prinz’s genealogical method has a potential risk of being myopic and thus needs to be repositioned.

After these presentations, Prinz made insightful replies to each presenter. At the end of the workshop, Profs. Nobuhara and Prinz made closing remarks. We faithfully promised to cooperate with each other in our future research.

Mineki Oguchi (UTCP research fellow)