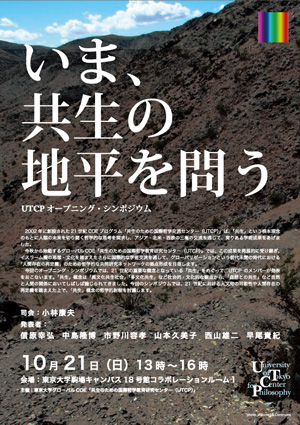

UTCP Opening Symposium, "The Horizon of Co-existence Today"

We had the opening symposium of the UTCP on October 21. Below is a summary of the report originally written in Japanese.

Yasuo Kobayashi, the director of the UTCP, began the symposium with the following remark: This symposium is smaller than the opening symposium of the first term UTCP held five years ago; however, this reflects our will that the UTCP should be more organic and powerful. The UTCP must be a place for members who examine and discuss philosophical problems beyond disciplinary boundaries. The first thing that we should discuss is the very idea of "co-existence" that the Japanese official name of the UTCP has.

The first presenter, Yuji Nishiyama gave us a historical overview of the notion, "co-existence." He examined how related notions such as symbiosis and convivilaity were discussed in relation to nature or society, and argued that we need to consider what co-existence should prohibit and to avoid it: the logic of sacrificing ourselves under the name of co-existence.

Kumiko Yamamoto introduced the recent work of Abbas Kiarostami, the Iranian film director, to consider the co-existence of the world where people have faith and the world where people have no faith.

Yukihiro Nobuhara discussed a problem that his program "Brain Sciences and Ethics" deals with. The problem is how we can co-exist with the neurosciences, in particular, the recent development of technology that reveals how brain works.

Takahiro Nakajima compared two Confucian conferences in 1935 (Japan) and 2007 (China), and discerned a similarity between them. In both conferences, the importance of harmony was stressed. He warned against such a move because it does not take the idea of justice seriously.

Folloing Ilan Pappe, the historian, Takanori Hayao argued that we can still see the violence that we saw when Israel founded its nation. In Hayao's view, it is related to Japan in a sense. According to him, Israel use the "thought of blood" to distinguish between Jewish and Arabs. Japan also adopt the same "thought of blood" to diferentiate between Japanese and foreigners, and the idea of co-existence mentioned in Japan is often based on a sheer prejudice against foreigners. Thus we cannot talk about co-existence without scrutinizing what it means.

Yasutaka Ichinokawa talked about three points in relation to co-existence:

1) The history of exchange between Japanese and German medicine helps us to reconsider the asymmetry of power that knowledge has. 2) Disability studies examine how society that deprives the disable of many possibilities works, and thus aim at undermining the boundary between society and the disabled. 3) Co-existence can include a political struggle where Gandhi's idea of nonviolence is helpful. Everyone can participate in a nonviolent struggle. When we think about co-existence, we need to examine the potential of nonviolence as a means to justice.

As described above, each presentation considered the idea of co-existence from different perspectives, and thus revealed problems that this idea has. Justice and struggle are necessary for co-existence. Yet, without reconsidering them, talking about co-existence is a kind of lip-service. But we cannot abandon the idea of co-existence. Thus we have to give concrete contents to it. This is what Kobayashi's concluding remark, "The UTCP organizes a nonviolent struggle," means.

(Originally reported by Jun-ichi Kushita and Dan Morita; excerpted and translated by Kei Yoshida)